What a great read this is. Cartwright assembles a wonderful cast of characters in this masterpiece of a comic novel. The aristocratic, family-owned bank of Tubal & Co is one of the City of London's finest – and oldest – financial institutions. But since Julian Trevelyan-Tubal took over as chairman after his father Harry's stroke, the 340-year-old bank is in trouble. After getting caught up in hedge funds and all manner of other ill-advised investments, Julian is secretly putting the bank up for sale, while attempting to shore up assets by temporarily and disastrously diverting millions of pounds.

The elderly Harry, meanwhile, slowly dying in Antibes, is still firing off warning shots about the dangers of reckless lending, unaware that the damage has already been done. As he looks across the bay from the family villa, he gazes fondly at his beloved yacht, sold off without his knowledge to a Russian oligarch as part of Julian's rescue package. Harry's younger second wife Fleur, disgusted by his illness and old age, has given up on him and relinquished his care to Estelle, the housekeeper-confidante who has her eye on Harry's £30m Matisse. In turn Fleur is risking her own stake in Harry's will by cavorting with a South African personal trainer in the broom cupboard at the local gym. As the days pass and urgency grows, Julian, the son who had never wanted any part in the family business, finds himself driven to increasingly desperate lengths to cover up a growing financial hole.

Then, in another part of the world entirely – a sleepy Cornish backwater – something happens that threatens to bring the entire bank crashing down. The monthly allowance paid to Fleur's shambolic theatre-director ex-husband Artair MacCleod does not materialise. Eccentric and maverick, MacCleod's true dream is to complete a screenplay – for Daniel Day-Lewis, he imagines – but, more pressingly, the sudden lack of funds threatens his current children's production of Thomas the Tank Engine. His complaints to a local cub reporter, Melissa, turn into a bigger story when the paper is tipped off by an anonymous source that MacCleod's monies aren't the only disappearing funds on Tubal & Co's balance sheet. Melissa's editor, himself badly burned during the Maxwell era, smells blood.

All of these characters are drawn with fondness, uncanny realism and an unwavering ear for amusing, authentic dialogue. Cartwright's delight in language is infectious: I particularly relished the idea that the creepy Estelle carries with her an "old-lady microclimate". The portrayal of the bonkers Artair MacCleod is extraordinarily brilliant: he is lovable and ludicrous at the same time, painstakingly sealing his letters to Daniel Day-Lewis with wax – "some falls, inevitably, on to the remains of an Asda quiche."

As well as being funny and clever, this novel is also a handy idiot's guide to the financial crisis. And who doesn't need one of those? "The City fell in love with the notion of frictionless wealth," Cartwright concludes , using Harry's complaints to show how out-of-control things got according to the old standards: "You can go on calling them derivatives until you're blue in the face, my boy, but show me one." Julian is largely responsible for the crisis in his own bank, which he has caused thanks to a mixture of inexperience, greed and insecurity. The title refers to the reckless, gloating shout that used to go out across trading floors when a deal went bad: it's all "OPM" (Other People's Money).

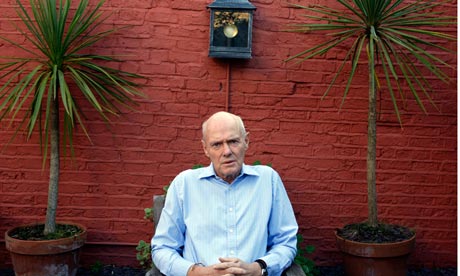

This novel really shows that to his credit Cartwright is a difficult writer to pigeonhole. Booker-shortlisted for In Every Face I Meet, his 12th novel The Promise of Happiness was a hugely popular Richard and Judy Book Club pick. Other People's Money is in a class of its own: both commercial and literary at the same time. The book falls into the same sort of territory Kate Atkinson is now mining to great effect: a read as enjoyable as it is intelligent, without pretensions and not straitjacketed by genre. Without exaggeration, Other People's Money just felt to me exactly like the novel I wanted to read right now.

Cartwright's subject matter feels incidental and not remotely bandwagon-ish. Quite a feat given that the whole book is about the financial crisis. This is a modest, gentle work of genius which creeps up on you. It's also the only time a book has ever caused me to laugh out loud with sheer joy on the very last page. A treat from start to triumphant finish.