About five years ago I went to Eastwood to give a lecture on DH Lawrence. Before the lecture I was taken on a tour of the Lawrence birthplace museum where there was an exhibition of various bits of Lawrentiana, including a couple of framed letters he'd written. In the solid setting of frame and museum there was something intense and fragile about these delicate sheets of paper, covered in the author's flowing, old-fashioned hand-writing. I felt the stirring of an entirely new desire, and wondered if it might be possible to own a letter by Lawrence. As is the case with most desires, this one was not acted on and, by being left alone, it went away. Sort of.

My wife works in the art world so we know quite a lot of artists, art collectors and gallerists. Pre-credit crunch, we were constantly being tempted – not least by stories of the fantastic profits to be made by acquiring something and flipping it a few months later – to buy art. This atmosphere of fashionable covetousness kept reminding me that there was something I wanted to possess, to own and hang on a wall.

It wasn't just covetousness. Lawrence has always meant a great deal to me and, more than a decade ago, I wrote a crazy book about him. My desire to own a letter, in fact, was in keeping with the tacit critical position outlined in that book.

As time goes by we drift away from the great texts, the finished works on which an author's reputation is built, towards the journals, diaries, letters, manuscripts, jottings. This is not simply because, as an author's stature grows posthumously, the fund of published texts becomes exhausted and we have to make do with matter never intended for publication. It is also because we want to get nearer to the man or woman who wrote these books. A curious reversal takes place. The finished works serve as prologue to the jottings; the published book becomes a stage to be passed through – a draft – en route to the definitive pleasure of the notes, the fleeting impressions, the sketches, in which it had its origin.

In the case of Lawrence this process coincides with the gravitational pull of his work, which is always away from the work, back towards the circumstances of its composition, towards the man and his sensations. As is so often the case, it was his wife, Frieda, who best captured this: "Since Lawrence died, all these donkeys years already, he has grown and grown for me . . . To me his relationship, his bond with everything in creation was so amazing, no preconceived ideas, just a meeting between him and a creature, a tree, a cloud, anything. I called it love, but it was something else – Bejahung in German, 'saying yes'". This saying "yes" is heard most clearly in Lawrence's letters. It is audible in the novels, too, of course, but it becomes more pronounced, more exposed, as we descend the traditional hierarchy of literary importance.

It is for this reason, I think, not simply because of his fame, that Lawrence's manuscripts became so sought-after. His writing urges us back to its source, to the experience in which it originates. We want the experience of reading him to be as intimate as possible; for the collector – for the kind of person I was poised to become – this means unmediated even by type-setting. Frieda had as sharp a sense of the potential commercial value of the Lady Chatterley manuscripts as anyone, but she also understood and expressed perfectly the poignancy of this intimacy: "I enjoy looking at them," she said, "and reading them in the raw."

For his part, Lawrence was not particularly attached to his manuscripts, though as his fame spread and his health failed he became conscious that they could serve as "a sort of nest egg". After Frieda gave Mabel Dodge Luhan the manuscript of Sons and Lovers in exchange for the ranch near Taos in New Mexico where the Lawrences lived – off and on – from 1922 to 1925, she heard that, whereas the ranch was worth a thousand dollars, the manuscript "was worth at least $50,000, at least!" (That gleeful repetition!) Thereafter Lawrence decided he "ought to be more careful of the rest of my MSS".

Easier said than done. In 1929, living in Italy again, the Lawrences learned that their friend Dorothy Brett (who was still in Taos) had sold a manuscript – they became convinced that she was going to flog off the rest of the contents of a cupboard at the ranch. Soon he and Frieda were writing accusingly to Brett, demanding that she provide a full inventory and then put the papers in a safe deposit box at the bank. Brett was slow in replying and the Lawrences' accusations soon turned to abuse. When the list did arrive it appeared far from complete and Lawrence became convinced that he was being swindled. Inured to Lawrence's wild changes of mood, Brett was not unduly concerned. "When a basically careless man like Lawrence becomes careful – & has no track of his carelessness – he is apt to fly of the handle," she explained to a friend. She was absolutely right: most of the "missing" manuscripts were already safe in the office of Lawrence's agent, Curtis Brown, in New York.

Lawrence wrote a lot – even on days when he claimed to be too ill to work. The magnificent Cambridge Edition of the Collected Letters runs to seven volumes, each of four or five hundred pages. By the time this great project of literary scholarship was completed a further 150 letters had come to light and so a supplementary eighth volume was added. In total, that's about three and a half thousand pages of letters.

I assumed that most of these were in institutions, but it took only a bit of Googling to find that there were still quite a few on the market. I contacted Michael Silverman, a dealer based in south London, and one Sunday he turned up at our house with half a dozen letters. The cost varied according to length, "content" and who they were addressed to. Of the ones on offer the longest and most expensive was to Katherine Mansfield (21 July 1913). I didn't care about length, and for content I could refer to the Cambridge volumes. I just wanted something – anything – in Lawrence's hand. Mr Silverman had just the thing: a note dashed off by Lawrence to thank someone for sending him a book. It could be mine for £1,200. Which worked out at about 80 quid a word. For Lawrence, this would have been an unimaginable fortune.

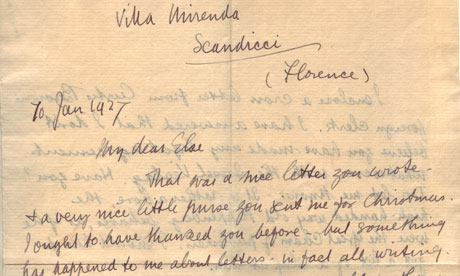

Mr Silverman said that for a little extra I could get a letter that did say something interesting. There were two that I particularly liked, both to Else Jaffe, Lawrence's sister-in-law. One, written on 31 January 1928, contained the admirable claim "'I'm sick to death of literature'." The other, written on both sides of a single sheet of paper, signed "Auf Wiedersehen, then, DHL", was dated 10 January 1927 when the Lawrences were living at the Villa Mirenda, near Florence. Not for the first time Lawrence says that he is "losing my will to write altogether: in spite of the fact that I'm working at an English novel" (the second version of what would become Lady Chatterley's Lover). The great lines come near the bottom of the first page, where Lawrence writes: "Painting is more fun than writing, much more of a game, and costs the soul far, far less." This sentiment invited an obvious rejoinder – "Yes, painting like that costs the soul far less" – but to me, a writer who had always envied the lot of the painter, it made perfect sense.

But actually buying this letter – forking out fifteen hundred quid for something I could read, any time, on page 621, volume V of the Cambridge edition – made no sense at all.

Cars and houses cost a lot of money. A car has an engine, glass, electrics, raw materials; but instead of saving up to buy a solid and useful piece of engineering like this I was going to buy a flimsy piece of yellowing paper that was entirely superfluous. I was reminded of a conversation in New Mexico when my wife and I were hoping to buy a Navajo rug. "Why is it so expensive?" my wife asked. "Because it's very valuable," came the reply. Lawrence considered his first sight of New Mexico "the greatest experience from the outside world" he had ever had. This conversation was the greatest experience of the price mechanism I had ever had. Here was the tautologous circuitry of the art market in miniature. Why does this cost so much? Because it's what we can get for it, sucker!

Buying a Lawrence letter was both ludicrous and completely out of character. I've never wanted to own anything except books, of which I have a great many. Some of these happen to be signed first editions, but they don't get special treatment because of that. If you wanted to borrow my copy of Tobias Wolff's Old School (Knopf, hb, first US edn, vg, inscribed by author) you'd be most welcome. I would take the cover off as a kind of deposit and reminder; it would be made very clear that this was a loan, not a gift, but once you agreed to these terms and conditions you'd be free to take it. For a fortnight. It's nice having things like this, but the crucial thing about my library is its considerable utility value. I can look up quotations, refer to things.

But now I was going to move beyond any kind of necessity into a realm of non-utility, pure collecting. And this would involve an entirely altered relation to money. The only precedent I'd had for this was when I fell victim to a Mamet-style con and lost the $2,000 deposit I'd paid to rent an apartment in New York that didn't exist. The practical consequences were soon repaired – I found another apartment – but I kept thinking about what I could have done with the missing two grand. To get over it, as they say, I had to come to the same realisation that would enable me to buy this letter by Lawrence, something that, at the deepest level of my being, was unthinkable: namely that, in spite of the hundreds of small economies which had, over the years, become second nature, I might, aged 51 (seven years older than Lawrence at the time of his death), be comfortably off.

So I did it. After negotiating a 10% discount I wrote a cheque for £1,350 and took possession of a fading bit of secular scripture.

I was then faced with the problem of what to do with it. I have always been reluctant to own art on the grounds that after a couple of days it grows invisible. A friend once told me how someone he knew had for many years craved a certain painting by Jackson Pollock. The moment he finally got his mitts on it was like a dream come true. After that, apparently, he looked at the painting for about 10 minutes. That sounds a little premature, but the general point stands: the only time you really notice a work of art you have looked at day after day is the day after it's been stolen.

I spent an hour or so touching this literary relic, looking at it (it never occurred to me to read it). Then I had it mounted in a double-sided frame and hung it on a wall in my study. If I glance up I can see it now. Obviously I can see only one side of the letter, but if I want to I can take it down and study the reverse side, or show it to friends. The letter has no talismanic or totemic value – it hasn't made writing any easier – but I absolutely love it. I've not regretted buying it for a second.

Gazing at a photo of Napoleon's brother, taken in 1852, Roland Barthes realised: "I am looking at eyes that looked at the Emperor." During the period I spent fondling my letter I was acutely aware that I was holding a piece of paper that, more than 80 years ago, had been held and written on by DH Lawrence, who, irrespective of what you think of his poems and novels, was surely one of the most remarkable men of the 20th century. Even now that it's hanging untouchably on my wall the letter retains this tangible, palpable quality. What my wife said in the immediate afterglow of the consummated transaction, still holds good: "It's as if he's writing to us."