The Greenes were (and are) a family of conspicuous qualities (not least that they are all very tall) and there are more of them around than you might imagine. A century ago, two brothers settled in Berkhamsted, a small country town in Hertfordshire. One was Charles Greene, the headmaster of Berkhamsted school, who lived in the school house; the other, Edward Greene, a highly successful coffee importer returned from Brazil, who lived in some splendour at the hall at the other end of town. Each had six children and Jeremy Lewis's entertaining group biography examines how this influential generation of cousins helped shape the course of the 20th century.

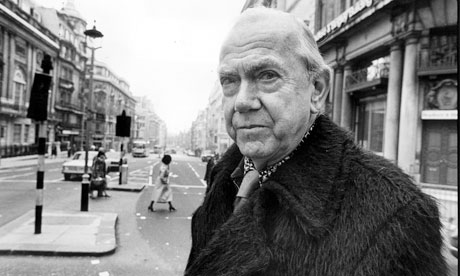

Graham Greene is, of course, the most famous. After a shaky beginning, he was a bestselling novelist by the time he was 28 and remained so until his death in 1991. He became rich, famous, often tipped for, but never winning the Nobel prize, a restless traveller in dodgy parts of the world (notably in Liberia with his feisty cousin, Barbara), partial to drink and women, politically contrarian, anti-American, a Catholic convert, a sometime publisher and spy (recruited by his sister, Elisabeth), and a constant friend of Kim Philby. He was one of the "School House" Greenes – among family and friends they were characterised as cerebral and with a quality variously described as shyness, diffidence or coldness, depending on the degree of partiality.

Hugh was Graham's youngest brother and the one to whom he was closest. He made a name for himself as a foreign correspondent in Berlin reporting on the Third Reich, and during the war was in charge of BBC broadcasting to Germany. He remained at the BBC after the war and served as director-general from 1960 to 1969, modernising the organisation in the midst of considerable social change. His tenure can now be seen as one of the corporation's finest hours.

Herbert, Graham's oldest brother, had briefly served in the ranks in 1918. Afterwards, he fell into the role of black sheep and remained in character for the rest of his life. Hard-pressed to keep a job, always running up debts, starting over, failing again, drinking a bit too much – he became an object of constant exasperation to his parents and siblings, though they always supported him, with Graham taking over financially after his parents' death. (Herbert became the model for several of Graham's feckless antiheroes, such as Anthony Farrant in England Made Me.)

Raymond, the next oldest son, became a mountaineer, participating in two Everest expeditions, and a world-renowned endocrinologist. While an undergraduate at Oxford in the 1920s, Raymond's adventurous spirit drove him to track down notorious occultist Aleister Crowley, the "Great Beast", in Sicily. Raoul Loveday, a fellow undergraduate, had died at Crowley's satanic abbey at Cefalù and the event had been reported in the English press with lurid accounts of orgies and "unutterable filthiness". Raymond set off in pursuit of the truth, and possible revenge on Crowley. However, "far from being a sinister, rock-hewn fortress perched on the brim of a gorge, the abbey turned out to be a whitewashed bungalow surrounded by olive trees; three normal and cheerful-seeming children were playing in the garden, and a Frenchwomen called 'Chummy' explained that the Beast was feeling unwell and had gone into Palermo to see a doctor". When Raymond returned later, Crowley was still not back. "Crowley's children were once again playing in the garden, and disappointed not to see their father, raised a plaintive cry of 'Where's Beastie? Why haven't you brought back Beastie?'" Raymond eventually concluded there was no scandalous murder to avenge and when he did meet Crowley he found him "disappointingly unsinister".

The "Hall" Greene cousins, by contrast, were known for their passionate engagement in causes and high idealism. Felix became an important creative figure in the early history of the BBC, notably setting up its American offices in the 1930s. A convinced pacifist and what we would now call new-age seeker, in the 1940s and 50s he became instrumental in the creation of the west-coast counterculture. Later, he grew enamoured of Maoist China and made many documentaries about it, his hope blinding him to its faults.

His brother, Ben, a fellow pacifist, was a key figure in the prewar Labour party, but his determination to prevent another war with Germany led him into compromising company. During the war he was imprisoned without trial alongside the fascist Oswald Mosley.

As the Crowley story indicates, Lewis has a first-class nose for truffling out good anecdotes, and there is a large cast of famous names and eccentric characters, including guru Gerald Heard and spymaster Maxwell Knight. It is to his credit that he doesn't try to force some overarching social or psychological theory on to these interesting lives – though there is certainly enough material in the Greene family for a sociological study of upper-middle-class transformation in the 20th century. But that might well be a far less enjoyable book.