Harvey Pekar carved a unique niche for himself within the spandex world of comics, often working with material from his own life against the backdrop of his native Cleveland. Pekar was arguably the first and best to use the medium to illuminate foibles, flaws and failures. With his death this week at the age of 70, visual literature bids farewell to a true American anti-hero.

Pekar was no artist – he was a writer through and through, as blue collar and geographically territorial as Charles Bukowski, and as idiosyncratic as Robert Crumb. It was a shared love of jazz that would lead Pekar and Crumb to first form a friendship and then a creative partnership that gave Pekar the break he needed. It was his stories, and not the crudely-drawn stickmen that accompanied them, that persuaded the then-established Crumb to be the first to illustrate the comic for which Pekar is best remembered, American Splendor.

And what stories they were. In an era – and medium – of superheroes, Pekar was anything but. Adopting the philosophy that "ordinary life is pretty complex stuff", his comics relayed the painful experiences of a creative-minded, penny-pinching curmudgeon at odds with the world, who floundered while working as a file clerk in a hospital, a job he held down even after his comic book success.

Pekar saw in comics an opportunity to create something akin to film, only easier, cheaper and quicker. His weary depiction of an existence spent scraping by in between failed relationships was shot through with the type of misanthropic humour that puts Pekar's work on a par with Woody Allen, Larry David or a supremely irate New York cab driver. And as with the very best anti-heroes, in his work no one came across quite as honestly as Pekar himself.

There was immense compassion and humanity in his work, too, and it is testament to the strength of his writing and characterisation – and his association with life's underdogs - that Pekar attracted a legion of collaborators which included comic titans such as Spain Rodriguez, Joe Sacco and Alan Moore. As well as enjoying a healthy sideline career as a jazz and book critic he became an unlikely national celebrity in the late 80s when he appeared on Late Night with David Letterman numerous times. His energised everyman views eventually became a little too much, and he was banned for criticising the show's owners. But it was this honesty and ability to see through the facile pretence of mainstream America represented by the likes of Letterman that endeared him to so many.

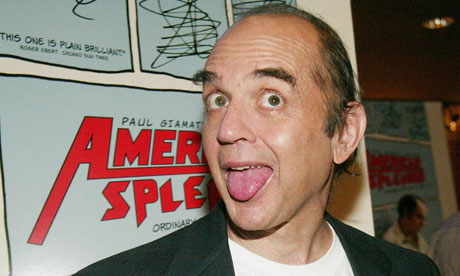

The 2003 film of his life, American Splendor, elevated him to international status when Paul Giamatti perfectly nailed his rasping rants, with Pekar himself popping up to comment on the onscreen depiction of himself in a fine piece of meta-cinema.

It's only in recent years that comics have been re-branded as the more intellectually-acceptable "graphic novels" and finally gained the critical and academic attention they deserve. Unlike those of the counterculture generation, however, Harvey Pekar didn't want to destroy society or alter minds through comics. He wanted instead to write serious literature, and his work – perhaps more than anyone's – was key to this shift. His substantial output continues to show that comics long ago stopped being just for kids.