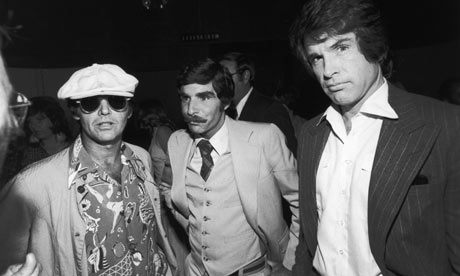

I have opened Peter Biskind's new book, Star: The Life and Wild Times of Warren Beatty, about the movie actor who 40 or so years ago was pretty much top of the international stardom tree. And now ... well ... a younger generation shrugs or looks blank at the very mention of his name. He's not a famously hard-worker like Michael Caine, nor a towering directorial presence like Clint Eastwood, nor has he established a legacy institution like Robert Redford with Sundance. His last movie was the dull romantic comedy Town and Country, in 2001, and since then he appears to have been in semi-retirement.

Biskind, although evidently exasperated by his subject's legendary secrecy, manipulation and control-freakery – Beatty appears to have given his biographer just as much of a run-around as everyone else – is still very much on his side. Part of his mission is to restore Beatty's reputation as a serious producer and actor, and to remind us of Bonnie and Clyde's sensational impact and of the boldness and ambition of his massive drama about John Reed and the Bolshevik revolution, Reds. He also makes a persuasive case for Shampoo as classic American comedy.

But somehow I find the most riveting thing about this story is Beatty's extraordinary duel with the New Yorker's legendary film critic Pauline Kael. A whole book of Jamesian subtlety could be written on simply this episode – or maybe, in some years' time, a biopic or BBC4 drama.

In 1979, Beatty made Kael a startling offer: to come and effectively work for him, producing a film called Love and Money, written by Beatty's friend James Toback. Perhaps dazzled, clearly flattered and possibly feeling stale, Kael accepted. She took a five-month leave of absence. Notoriously, nothing happened. The Toback project never got off the ground and Kael found herself in an office at Paramount, twiddling her thumbs, before eventually going back to the New Yorker feeling frustrated and sheepish.

If Beatty had genuinely been committed to reinventing Kael as a creator rather than critic, then this remarkable experiment could have succeeded. Kael could conceivably have had a secondary "boutique" career in movie production, like Vanity Fair's Graydon Carter later did. But Biskind seems to accept the prevailing view that all Beatty wanted, in the inmost labyrinthine depths of his mind, was to take Kael down a peg or two, to humiliate her, to show the upstart reviewer who the real player was.

Why? Was it because Kael was mean about him? She wasn't (though she was hardly a fan). In fact, it was her passionate support for Bonnie and Clyde that put Beatty on the map. And perhaps Beatty couldn't forgive her for that. Undoubtedly, his "producer" ploy drew blood, although it didn't silence her.

Nowadays, it seems extraordinary that a critic could have so much power. (I'm not expecting James Cameron to play mind games with me by offering me a producing gig on Avatar 2.) But then, Kael had such brilliance and passion that – who knows? – she might hold precisely the same sway if she were writing now.

There is something in Biskind's treatment of the episode that makes me uncomfortable: a persistent strain of anti-Kael propaganda, a sense that Beatty might have indirectly induced Biskind to disparage Kael all over again. Of her diminutive appearance, Biskind says she "could easily have passed for a small-town spinster"; he criticises her readiness to socialise with people in the business; he says she "was susceptible to the blandishments of stars, especially star-auteurs and glib writers who practised on her vanity". Most insultingly, he even claims Kael pinched other people's one-liners in conversation, quoting Robert Towne: "'She'd take out her notebook and say: "That's really good," and write it down. She'd be very bald about it.'"

Well, OK, all I can say is that I'd like to hear Kael's side of this. I can't, because she died in 2001. Beatty and sources close to him are, however, very much alive. Biskind has spoken to Kael's friend Richard Albarino to elicit the view that she had a schoolgirlish crush on Toback. I get the definite sense that the picture of Kael is basically a spiteful one, coming largely from the alpha-male boys' club with their prickly and eternally insecure egos. Kael was a powerful, critical woman, and when Beatty was a power in Hollywood, such things were intolerable.

It was a pretty nasty, sour episode. Beatty's reputation is lowered by it. Kael made a mistake in accepting his insincere job offer. But I think her reputation is undiminished.