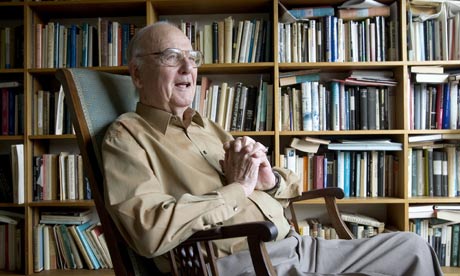

Frank Kermode recently celebrated his 90th birthday with the addition of these two books to his sizable corpus. In Concerning EM Forster, Kermode tells the reader that Forster "lived to be old and still active, an achievement that almost always impresses the public". The self-deprecation contained within this remark is characteristically subtle, dry and imbued with gentle exasperation. Kermode knows that the reviewers will once again acclaim him as Britain's greatest living literary critic, pointing to his erudition and astonishing output, his calm authority and easy eloquence. Kermode, born on the Isle of Man in 1919, is the last survivor of a golden age of postwar public criticism, though in some ways he is atypical of the earlier generation.

What differentiates him from FR Leavis, William Empson and TS Eliot is the mildness of his persona, an absence of fervour or mission. This is not to suggest a lack of faith in his own judgment, but, rather, that his voice is marked by a certain caution and tact. Kermode is tellingly fond of Lionel Trilling's remark about Forster: "He refused to be great." Perhaps this is because Kermode did not reach Cambridge until his 50s, arriving via grammar school and a string of provincial universities. It is not accidental that his 1995 memoir was called Not Entitled. His 10-minute encounter with the "great man" in 1955 was time "well spent" for Kermode, but Forster, "understandably tired and bored", would "probably have judged it differently".

To what extent this humble and self-effacing persona is a performance is a moot point. Kermode's voice is slow to anger, balanced, fair-minded and discreet, but this affords its own authority. He persuades us to listen by speaking quietly. This humility, the lack of an air of entitlement and hauteur, is one reason why the nonagenarian does not seem dated or out of time in a way which, arguably, a more mandarin and high-cultural figure like George Steiner now does.

Deriving from Kermode's 2007 Clark Lectures (which Forster had delivered 80 years previously), Concerning EM Forster is laced with submerged identifications between author and subject. Forster was also something of an outsider or marginal figure, simultaneously attracted to and repelled by the avant-garde experimentalism of his contemporaries. He had a dislike of system or theory and felt that Henry James's ruminations on the novel form were overly abstract and prescriptive. Likewise, the elasticity of Kermode's critical discrimination favours variety of effect rather than predefined artistic purpose. In their differing ways, Kermode and Forster embody the virtues of a liberal-minded Englishness, open-minded and capacious in sensibility, suspicious of over-abstraction, eager to be true to lived experience, including, crucially, the reality of death. For Forster, the recognition of death was an urgent necessity for the novel to achieve greatness.

Kermode is often at his best when giving into the occasional irritation, such as the snobbery he detects in Forster's depiction of Leonard Bast in Howards End. Among the richest pieces in Bury Place Papers are those where he finds fault with William Empson, who he prizes as the greatest critic of the last century, for attempting to shoehorn John Donne into his own anti-Christian belief system.

This selection of 29 essays – mostly reviews that Kermode contributed to the London Review of Books, the journal he played a key part in founding – gives a sense of the breadth of his learning. It starts with a piece on millenarianism from 1979 and, following a chronological sequence, ends with a 2007 review of Helen Small's book on old age. On the way, it takes in Flaubert, Wilde, Shakespeare, Raymond Carver and Kazuo Ishiguro, to say nothing of Howard Hodgkin, Noël Annan, Harold Nicolson and Donald Winnicott. An elegant introduction by fellow LRB regular Michael Wood precedes the whole. These pieces comprise a cornucopia of Kermode's critical acuity but also a history of modern letters.

There are memorable vignettes, such as the 74-year-old AE Houseman, ailing and tired of life, running up the stairs to his college room in the hope that he might expire on arrival. Occasionally I felt that Kermode pulled his punches. His review of John Carey's What Good Are the Arts? leaves him wondering if there is not "surely more to be said", while parts are "probably over-simplified". Perhaps the big beasts of criticism should not review each other. Yet his critical asides can be gloriously arch, even when wrapped in a compliment. "Martin Amis has always wanted to be a good writer and he has got what he wanted." This sentence economically evokes an image of the warrior against cliché rifling through the thesaurus, and Kermode gives us a choice selection of Amis's "recherché adverbs".

The judgments and reflections here are sound and wise. The final piece on old age is characteristically generous, reflective, layered and nuanced. It includes the wistful recognition that we cannot shape death into the reassuring pattern of narrative, cannot imbue it with the sense of an ending: "Death may be, is likely to be, a little too early or a little too late."