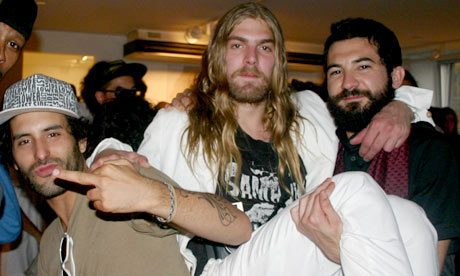

Dash Snow, the New York artist who died this month, was responsible for a rolling piece called Nest Project. It consisted of shredded paper, bodily fluids, and graffiti about bestiality, Abraham Lincoln's drinking binges and a "gang bang at Ground Zero". As one writer said after Snow's death: "He simply didn't give a shit." Most people would not regard this as praise for a working artist. Proper nihilists don't bother to make art, and if they were forced to do so – under, say, a community service order – why would they bother to make it any good?

Perhaps, as people said, Snow was just out to shock. What's wrong with that? Nobody seems to think there's anything wrong with art being poignant just for the sake of being poignant, or angry just for the sake of being angry, or beautiful just for the sake of being beautiful. So shock seems a perfectly legitimate effect. It is a slightly lumphammer approach, though, because shock is an unsubtle state. To be "in shock" means your faculties are more or less paralysed. These will tend to include the aesthetic, emotional and discriminatory ones. And if you've really shocked the audience, you may find yourself running out of moves. Soon you're playing the fire alarm, not the piano.

There's extremity of form (Stravinsky, free verse, cubism) and there's extremity of subject matter. They don't necessarily go together, though they often have. In literature, Burroughs, Ballard, Hubert Selby Jr and their like were formal experimentalists as well as experiential extremists. Shock comes in and out of fashion but largely has two purposes. One is to kick against internalised rules and formal conventions. The other is to kick against externally imposed norms, such as censorship and social disapproval.

What's interesting is that, when it comes to shock, the different arts seem to be out of phase with each other. The big shock of modernism arrived in verse, painting, music and dance at around the same time: the beginning of the 20th century. In terms of material and subject matter, though, the genres are all over the place. For the last few years, being shocking has been one of the qualities most prized by critics and collectors in the visual arts. Rotting meat, funny plastic kiddies with penises instead of noses, sex and drugs, self-exposure, bodily mutilation and so forth. While shock and going to extremes is still hotly important to the producers and consumers of fine art, other art forms – ones that have struggled harder with censorship and notions of decorum – seem to be well over it. Theatre's last major convulsion of shock was probably a decade or so ago, with work by the generation that included Sarah Kane and Mark Ravenhill.

Literature has left all this even further behind. Somewhere between Ulysses and the unbanning of Last Exit to Brooklyn, books established the right to say whatever they liked – and they now do so with gay abandon.

So why is it that fine art still seems to be fighting these battles? It was in fine art, after all, that these battles were first and most decisively won. You could look at a Courbet or a Schiele quite happily, while the Obscene Publications Act was still breathing down the necks of other artforms. It can't but make shock retro: artists whose primary concern is still to Question The Very Nature Of Art, end up playing more or less sterile variations on Manzoni's tinned poo and Duchamp's pissoir.

But hold. I don't want to piss on Dash Snow's grave. And yet – don't you think? – it's what he would have wanted.