In 1960, Philip Toynbee, novelist and principal reviewer at the Observer, placed an advertisement in the national press appealing for written contributions from those who felt marginalised by society. The book, Underdogs: Anguish and Anxiety, was published the following year. In among essays from orphans, criminals and the mentally ill lay my father's anonymous missive, The Self-Inflicted Wound. He was 46 at the time and the outlook was bleak: disaster-prone and with a talent for self-destruction, he was living in a dilapidated gamekeeper's cottage in the moorlands of Snowdonia, with no means of income and reliant on his expertise with a fishing rod or knife for sustenance.

"My world is not peopled by men and women," he wrote in Underdogs. "My realities are the weather, the possession or lack of a bottle of paraffin, the impending demise of a shirt. My assets are briefly enumerated: the knack of catching trout in small troubled waters; a handful of friends and enemies on whom I inflict a rasping tongue and a marshmallow heart. A brain stuffed hugger-mugger with literature. A skull full of rubble and a pen full of tropes."

That my father rescued himself from this peril can be attributed to his formidable talent for the written word. Ten years later he was heralded as "that prince of phrasemakers" on Fleet Street – it was he who coined the phrase "a legend in his own lunchtime" – and hailed as an exceptional literary critic and sports writer. Many would have been proud of such accolades. Not Dad. He wanted to write a novel. A great novel. The Great Novel. "I'll show you all!" he would bark at dinner parties, before scuttling off to the kitchen.

The novel filled his conversation, and his desire to write it at times reached fever pitch, plaguing his thoughts, jeopardising his marriage and dominating my childhood to such an extent that he almost put me off literature for life. So it is something of a surprise that I find myself writing this, and – like him – writing for a living. Perhaps it is the recollection of the inscription he wrote in my first dictionary: "Words are the breath and blood of life." This seems to be true for many Wordsworths. Yet for my father, words were both his salvation and his curse.

Literary achievement had come to him early. Born in Calcutta in 1914, he was a voracious reader, often bookworming under the bedclothes by candlelight. At Rugby school he won the 1930 Rupert Brooke prize for poetry; at Oxford his tutor, CS Lewis, recommended him for the prestigious Newdigate prize for English verse. Yet when a year into his studies a legacy came his way, he left, somewhat impetuously, to pursue a literary career. Inevitably, the inheritance was squandered. In 1938, he married and had two children, the war beckoned and his literary pursuits were put on hold.

My father volunteered in 1939, serving with an Indian regiment in Iraq, India and Malaya. He decided that to write to his young wife would only upset her, a misjudgment he would rue for the rest of his life. Demobilised in 1945 and divorced in 1947, by 1949 he found himself washed up on the Welsh borders. In an area rich with bohemian idealists he was put in touch with the novelist Jeremy Brooks, who was sympathetic to my father's literary aspirations and in 1950 invited him to stay with his family in the village of Llanfrothen in Snowdonia; a forgiving environment in which to embark upon his book. "Words are what I have," he wrote. "I have lived with them too long; we torture one another and practise small perversions to salt the darkness, partners in a marriage gone stale. But I feel I have a kind of dulled belief that I am being battered into the shape of a writer..."

Early morning, 1983, and my 10-year-old self is taking a cup of tea to my father's study in our house in Harpenden, Hertfordshire. He has been up for two days and nights, working on his latest review for the Guardian. He is 69 and had a heart attack a year ago. I knock and enter. The air hangs heavy with tobacco. The right side of his face is tan with nicotine from the perpetual corkscrew of smoke emanating from the cigarette that sits characteristically on his lips but remains forever uninhaled. His shirt is stained and singed on the plateau where his hefty stomach catches, invariably, a full three inches of ash. I brush the ash from his belly and on to a floor thick with crumpled drafts. Soon the house is filled with the distinctive sound of two-finger typing. When eventually he is done, he slumps downstairs, exhausted. Turning to me, he says, "This isn't proper writing, you know, old son?"

Ours was a fractious relationship. By turns fierce, loving, overgenerous and overprotective, he was a mass of contradictions, his explosive temper a protective shield for his "marshmallow heart" as well as a symptom of his frustrations. Often we would argue about my reading habits. I liked Enid Blyton. He suggested Dickens. My reading ground to a halt aged 10. "Why do you think I keep all these fucking books?" he would say. As I got older I would taunt him back about his "novel", all the while aware that to make him angry was bad for his heart.

He had long struggled with the application necessary to bear literary fruit. By 1952, anxious to pay his way with the Brookses, he took a job in a cafe in Portmeirion. There he met Sue Amberley, daughter of the poet Vachel Lindsey and wife of John Russell, son of the philosopher Bertrand. They quickly fell in love and in 1954 moved in together. Weeks into their cohabitation, Sue inherited £8,000 from her father's estate. The urge to write slipped quietly on to the back burner as the two of them embarked on a five-year spending spree, with the cream of local bohemia lavishly entertained most nights. Yet the sheen of high living masked a more sinister reality. Sue's behaviour was becoming increasingly erratic; she would wander off into the Welsh hills for days on end, or attack my father with whatever was to hand.

He wrote of their love affair: "The last and loveliest with whom I shared my life left me 18 months ago, accompanied by what is technically known as the Duly Authorised Officer. It lasted five years, and those who had known for years that she was a paranoid schizophrenic but had not thought to mention it, did not concede it a chance to endure six months. She is dowered as few can hope to be, and flawed beyond despair. But live on. There will not be a time when I shall not remember you." The novel, needless to say, was no closer to being written.

Saturday evening, winter 1984. Outside our house the rumblings of a taxi. A car door is slammed followed by the familiar shout, "Good luck with the book, Mr Wordsworth!", words I hear mostly when my father tumbles out of taxis. A key scratches around the lock and a rough-hewn figure spills into the house, lubricated via press-box generosity from a rugby or cricket match that he has been covering for the Observer. The well-wishings no doubt spring from a charitable tip, soon to be expensed.

My father's study was a hinterland of illicit treasures: books on sex, mysterious medicaments, rows of Wisden and half-filled notebooks. One evening in 1985 I went through the notebooks, tearing out the spoiled pages, creating five fresh jotters for school. Proudly I showed my mum. "Oh my God," she declared. "What have you done?" What had I done? "These are the notebooks he writes book ideas in," she said. "We mustn't tell Dad. He'll go berserk." I put them back. Nothing was ever said. Occasionally I dared to ask him about the book he was writing; he told me only that it was "a novel about a man trying to write a novel".

After Sue's sectioning, my father was once more alone, and homeless. After spending much of 1959 moving from friend to friend, Brooks and two others, their belief in his abilities unstinting, rented him a cottage in the Migneint, a huge, undulating area of moorland miles from human contact. Yet my father's time, instead of being devoted to writing, was now taken up by the acts necessary to stay alive: the local trout stream kept the edge off his hunger, and when it disappointed he would poach or reappear at a friend's door, tail firmly between his legs. "Time that was once the dog at my heels," he wrote in Underdogs, "is now the wolf at my throat." It was, however, while up in the Migneint that, alerted to Toynbee's request, he submitted his essay.

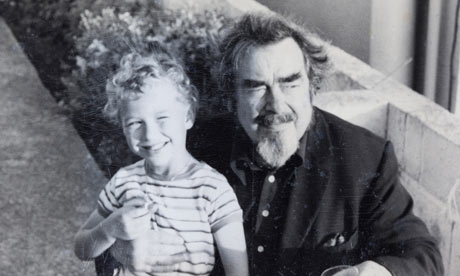

Underdogs was serialised in the Observer and reviewed to great acclaim, my father's contribution singled out for special attention. On the strength of those 18 pages the advance for a novel was proffered, though much of it was, I fear, splashed up against the nearest wall. Offers of journalism drew him to London and a new life, though not before he squeezed in a second wife and a third child. Finally extricating himself from north Wales in 1963, he moved to Barnes in southwest London and began writing regular book reviews. Then in 1970 he met and married my mother, Tamara Salaman, an Observer reviewer herself and 20 years his junior. I was born in 1972 and the three of us moved to Harpenden in 1975.

Despite his claims to despise suburban living, I believe the next 20 years were my dad's happiest. He and my mother enjoyed a great sparring partnership and were mainly happy. She tolerated his explosions, puncturing his pomposity with humour and even joined the book brigade, talking wistfully about the jelly recipe book she planned to write. During this period my father successfully reconnected with one of his older sons – the other shunned him – and derived considerable pleasure from my development, particularly on the rugby and cricket field. Yet the book, incredibly, still lived on: the taxi conversations, the notebooks, the wearing down of my mother ("How can I remain in Harpenden and write?"), such that their removal to mid-Wales in 1996, when he was 81, was to be a coming home of sorts, and a place to make good on his words.

It never happened. Within 12 months my mother fell ill. After years spent preparing me for his own death ("This will be my last Olympics" was his refrain in 1984, 1988 and 1992), he was felled by her cancer but fought on gamely, tending to her needs and nursing her back to some kind of health. He eventually died, in a room stacked high with review books, in 1998, aged 83. She lived on for another three years.

I do not mock my father's failure to realise his ambitions as a novelist. He was an astonishingly good writer, but it seemed that for all his abilities, he suffered from writer's block – to such an extent that "unless he thought it was going to be better than Tolstoy, he wouldn't commit it to paper", according to Brooks' wife.

Clearly at some point in the past there was a book to be written. Increasingly it acted as a kind of crutch, propping the door ajar through which hope could stream. "I succumb from time to time to the comforting theory of the Last Laugh," he wrote in Underdogs. What is the great unwritten novel but the threat of the Last Laugh, a comfort blanket against mediocrity, the pipe dream that sustains the dreamer? As for the Wordsworths' famous gift for words, it was only weeks before his death that he discovered he was not, in fact, related to William. The many ironies of his name were not lost on him.

In the last few years I have had to work fast. His friends are an elderly, dying breed. Four years ago I knew nothing of his early life. Now I have a host of interviews under my belt and a wealth of information about what was a fantastically romantic, if frustrated, life. And I have my own memories: his liver-spotted hands, our cooked breakfasts together, the distinctive "plop" of the latest review copy hitting the floor during his customary afternoon doze. I also have the notebooks he kept in the 50s; his handwriting has so far defeated me, but I hope in years to come to unlock more of his secrets.

I rarely took note of his words as I grew up. We saw eye to eye on very little, though by his death had agreed to disagree. Now I would gladly turn back the clock to have but an hour in his company; to pick his brains about his extraordinary life, experience afresh his overwhelming humanity and eavesdrop on the brilliance of an ever quotable tongue. He is gone, but my world is much richer for having been in his.

A longer version of this article can be found at saulwordsworth.com