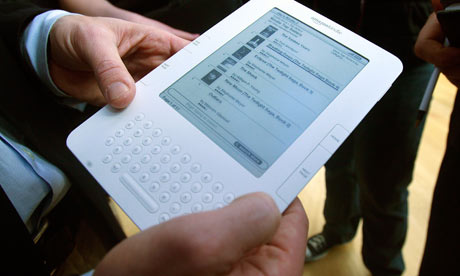

Under a post I wrote last week touching on the future of publishing and emerging ebook technology, a commenter (whom I can now out as Paul Emmanuelli, since he deserves credit for the ideas in this piece – the good ones, anyway) pointed out that so far most of the debate focused on how pleasant (or not) they are to use and "the End of Books as we know them" ... But there is so much more involved.

He asks of the Kindle, for instance, "What will its impact be on high street retailers? Does it open the back door for Amazon to become a monopolist retailer (and then publisher)? – Will the price of digitised books be driven down to the extent that margins/prices on hard-copy books are pushed up? – Where does the author stand in all this?" He also raises interesting questions about the potential benefits such travel-friendly devices might yield ("Could this be the rebirth of the serial and the short story, where commuters read the latest release on their way to work and talk about it when they arrive?") and about how the devices might be used to breed brand loyalty for publishers and writers.

Clearly, it's a debate worth having. It seems that ebook readers are on the way, no matter what we think of them, so we're going to have to work out how to use them to the best advantage of everyone involved.

Yet bowing to the inevitable as far as ebook readers is concerned is not something that should be done lightly, especially in the light of stories such as this: Late last week, several books downloaded by US Kindle users were deleted in the wake of a copyright issue. The first most users knew about it was when these books disappeared from their devices – a particularly disconcerting experience, one imagines, for those who were midway through 1984 – since, of course, the gods of irony had ensured Orwell was on the list of books deleted.

An Amazon spokesman responded to the Guardian's Bobbie Johnson, saying: "These books were added to our catalogue using our self-service platform by a third-party who did not have the rights to the books … When we were notified of this by the rights holder, we removed the illegal copies from our systems and from customers' devices, and refunded customers."

Johnson continues: "Amazon refunded the cost of the books, but told affected customers they could no longer read the books and that the titles were 'no longer available for purchase'." Amazon later said they are changing their policy so that they don't delete copies of already-downloaded books in future – but that's not the point. We should fear the Kindle because something that can so easily effect alterations to texts is clearly open to abuse.

Digital copy is not set in stone – or even paper. As this story has shown, if someone wants to stop you reading something and they have control of the device you read it from, it's all too easy. What's to stop political interference? What's to stop vested interests changing history – or at least history as it's reported? It's been tough to make books disappear in the past because they tend to be scattered so far afield. Now, it seems, words can vanish at the flick of a switch.

This early Kindle book-burning episode also provides a reminder of how closely ebook devices monitor their users' reading. And that provokes quite a few questions. What's to stop advertisers paying to find out about your preferences, for instance? What's to stop churches finding out about people reading pro-choice literature in their area? What's to stop governments finding out about your revolutionary reading preferences?

The question of whether it is safe or wise to blithely hand over so much of one of our most important industries and so many of our treasured freedoms to the gatekeepers of this revolutionary technology is an entirely modern one. The issue that underlies it, however, is one of the very oldest: who will guard the guards?

OK, the sinister manipulations I suggest above are improbable (if not entirely impossible in a country threatened by ID cards and which no longer contains David Kelly). But even aside from such possibilities, the digital dights management technology employed by ebook readers such as the Kindle presents other concerns. These have been dissected in detail on the excellent boing boing and I find it hard to argue with Cory Doctorow's central complaint that DRM prevents you from truly owning something that you have, er, paid to own. I also share Paul Emmanuelli's fear about the monopoly DRM software could grant Amazon. If the Kindle achieves the same kind of market dominance Apple has with iTunes, it could have disastrous consequences. Effectively, there would be only one publisher; one gateway between writers and the public. And if you're an author and Amazon doesn't like you, or hasn't heard of you, you are – let's not mince words – screwed.

The non-DRM alternative doesn't seem much better. As a gleeful would-be copyright thief pointed out under Bobbie Johnson's article, if you have a reader that supports non-DRM formats "you never need pay for a book again." So how would anyone ever earn a living from writing?

It seems we are trapped between a rock and a hard place.