Colin Robinson has been in publishing since 1976. He has worked for fusty companies and radical ones, for earnest independents and empire-building corporations, for Britons and Americans: as an editor, always involved in the slightly precarious business of putting out serious books. But recently he started noticing something about the way books are treated that disturbed him. "Here in New York" - Robinson lives in a fairly intellectual part of Manhattan - "books are quite often left out in the street. If people are moving, they don't take their books with them."

There may be a harmless explanation. Manhattan apartments are small. Some people always get rid of books once they've read them. Yet Robinson has some cause to see the phenomenon as a symptom of something ominous. On 3 December last year, despite what he describes as an editorial list "filled with erudite, well-written books", he abruptly lost his job at the American publisher Scribner.

So many other editors were sacked in New York that day, it almost instantly became known in the closely connected worlds of American and British publishing as "Black Wednesday". In recent months, such culls have become grimly routine in many industries. But among those who write, publish and sell serious non-fiction - the biographies, histories, travel and science books researched and written with a degree of subtlety for a general audience - the bad news seems to have been building up since long before the current recession.

The range of titles stocked by British libraries has been falling for decades. The net book agreement, which in effect subsidised the British book business, has been dead for a decade and a half. In that time, book retailers have concentrated increasingly on the genres that are easiest to sell. Book prices have collapsed. Within many publishers, sales and marketing considerations have come to trump editorial ones, and most authors of serious non-fiction have had to accept smaller advances and smaller print runs.

Meanwhile, review space for their books in most newspapers has shrunk. The time their work spends on the shelves of bookshops has shortened. The competition for readers' attention - from the internet, from secondhand books sold online, from the seemingly ever-expanding celebrity culture - has sharpened. Bestsellers and "brand-name authors" squeeze out less established titles and writers more than ever before. Supermarkets and chain bookshops squeeze out independent booksellers. The number of books published in Britain - well over 100,000 a year and growing, five times as many as in 1970, which is far more than in comparable countries - means that all books fight for air. The computerisation of British bookselling, more advanced than almost anywhere in the world, casts an increasingly cold eye on serious books' commercial performance.

At the same time, wider cultural shifts - the evaporation of the idea of a literary canon, a less deferential attitude to experts, changing reading habits in the digital age - may be making serious, would-be definitive books less attractive to a broad public. Once-thriving serious genres such as political memoirs, literary biography and literary travel writing all appear to be ailing.

"The fat years of the printed word are over," says John Sutherland, the academic and author of several books on the history of publishing. "Even if books get dirt cheap, readers simply don't have the time or motive to invest in them. The old cultivated readership is not as solid as it was. The safe library sale doesn't exist any more. There's been a loss of authority in the serious book." A former bookseller who is now a freelance literary publicist says: "There are plenty of good books going missing. Books that take five years to write. Publishers used to put them at the front of their catalogues. Nowadays the print runs are tiny for these books, about 2,000. Publishers say they can print more copies, but if they're printing 2,000 of something they're not going to get behind it. Because of publishers' falling profit margins, production values have gone down on some of these books. You're seeing paper that's turning yellow before it gets out of the shop. You've got publishers and literary agents blaming the bookshops and vice versa. You've got people going to literary festivals who'll pay £10 for a ticket to an author event but won't pay £20 for a history book."

Neil Belton, an editor at Faber with a long track record in serious non-fiction, is almost as bleak: "The book trade and publishing industry has embraced its inner philistine. The bigger book chains have semi-withdrawn from interest in serious books. The number of publishers that are committed to trying to bring these books to an audience is smaller. When they are interested in serious authors, the big publishing conglomerates are often chasing only the very big names, people established in their fields." The literary agent Peter Straus, previously a publisher at Picador, is also worried: "It is more and more difficult to place good books. Retail's changed. Advances have come down in the last two years. So many books haven't sold. There are too many books published. The harsh realities of the market will impinge on certain writers, certain publishers, certain agents."

In his 2000 polemical history The Business of Books: How International Conglomerates Took Over Publishing and Changed the Way We Read, the veteran American publisher André Schiffrin calls this process "market censorship". But one person's market censorship is another person's market realism. Clare Alexander, like Straus a well-known agent previously involved in serious publishing, gives an example. "Between about 2003 and 2006, a lot of agents and publishers thought history was the new rock'n'roll. The advances people were paid were ridiculous: £100,000-plus for books that were not going to sell. Now the same sort of books are getting probably about £30,000. Some of the advances in serious non-fiction used to be seriously out of kilter."

Until 2006, Scott Pack was the head buyer at Waterstone's, Britain's most dominant bookshop chain. "Historically, publishers have published too much of this [serious] stuff," he says. "Fifteen years ago, there were tens of millions of pounds of unsold stock sitting in bookshops. A publisher would put out a book on Henry VIII, say, and distribute 10,000 up and down the land. Then the publisher would be sitting there saying, 'We sold 10,000 - didn't we do great?', when really only 2,000 copies of the book ever sold. Nowadays bookselling is more professional, more commercial. It's not as nice ... A bookseller can return unsold books to the publisher after three months. Or if the book is in a three-for-two promotion, after four weeks ... But we see much better what the true sales of serious books are."

Pack argues that those who fear for such titles in the modern marketplace are being snobbish and pessimistic. "In the last 10 years, the British book industry has been selling more books. More people are reading than ever before. Some of those extra readers are buying the kind of books you find in supermarkets - misery memoirs, mass-market crime - so, yes, the market share for heavyweight non-fiction will be smaller ... There used to be a lot of noise around these books. They were books made for great reviews. But people didn't want to buy them."

Currently writing a book blog called Me And My Big Mouth, Pack is practised at making populist, intellectual-baiting arguments. Elsewhere in our interview, he dismisses upmarket publishers and reviewers as "the intelligentsia" and unsold books as "dead stock" and "rubbish". Yet he insists that it is still perfectly possible for a good, serious book to find a readership: "The vast majority are stocked in ones and twos. They can stick around, pick up word-of-mouth, sell steady."

How such gradual success can be achieved given the ruthless stock control of the book chains is not something Pack explains. Yet some publishers of serious titles share his optimism. "The market for really good books has not diminished," says Stuart Proffitt, the publishing director of Penguin Press, identified by Schiffrin and others as a rare example of a corporate-owned publisher making a success of upmarket books. Proffitt cites Rosemary Hill's erudite biography of the Victorian architect Augustus Pugin, published by Penguin to great acclaim in 2007. So far it has sold more than 17,000 copies in hardback and paperback combined, according to Nielsen BookScan, the US market research corporation that records British book sales. David Kynaston's history of the Attlee era, Austerity Britain, has sold 65,000 copies; Kate Summerscale's reconstruction of a Victorian murder investigation, The Suspicions of Mr Whicher, more than 305,000; Richard Dawkins's anti-religious polemic The God Delusion more than 687,000.

Proffitt concedes that such successes take more effort than they used to: "You have to think more carefully than ever before about every aspect of a book's publication, how it looks, how you communicate its existence." But he insists that the fears for serious books are overblown. "People in the book business are always saying there's a crisis and we're going to hell in a handbasket."

On that point, at least, Proffitt has it over the doom-mongers. Book publishing is a melodramatic business: unpredictable, characterised by very public successes and failures, with even its seasoned practitioners consequently subject to sudden mood swings. In 1934, Geoffrey Faber, one of the founders of Faber, wrote despairingly: "The market is glutted. General publishing is therefore fast degenerating into a gambling competition for potential bestsellers." In 1979, the senior American publisher Jonathan Galassi warned that serious books were becoming "high-risk ventures for modern publishers who have inherited the overhead[s] of big business along with its management techniques and managers, and who have become increasingly reluctant to invest even very modest sums in projects which promise little in the way of immediate return". Non-academic publishing, he went on, may become "nothing more than the calculated marketing of slickly packaged materials, another 'leisure-time' industry ... unconnected to ... the intellectual and cultural roots of the society it purports to serve".

Today, such prophecies look both uncannily accurate and too apocalyptic. On the ground floor of the flagship branch of Waterstone's in Piccadilly, central London, the categories of goods on sale are listed on the wall as follows: "Bestsellers. Gift Wrap & Cards. Humour. Indoor Games. London. Magazines. Maps. Travel. Travel Literature." A huge, mural-sized poster advertising an in-store event by the entertainer Rolf Harris dominates the main entrance. Where books are on display, many of them are in the three-for-two promotions that, once restricted to deals on baby wipes or orange juice in supermarkets, have become central over the last decade to the operation of British chain bookshops.

But there is still serious non-fiction here and there. In recent weeks, there was a place in the front window for Iain Sinclair's chewy new history of Hackney, and a prominent table of thoughtful titles picked by Nick Hornby, including What Good Are the Arts? by the academic and critic John Carey. Esoteric history, the extended critical essay - both titles come from genres whose commercial prospects have been repeatedly written off.

And yet, something is undeniably shifting in the climate for serious books. You can see it in the Piccadilly Waterstone's and in the other cavernous chain bookshops along nearby Charing Cross Road, the traditional heart of British bookselling. Carpets and shop-fittings are worn. Shelves are half-filled. Customers are sparse, even on a weekday lunchtime. There is less bustle, less atmosphere, in these shops than when they opened a decade ago. There is a sense that good times have come and gone.

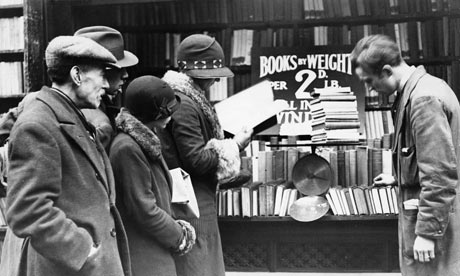

Good times have never been the norm for serious books in Britain. "From its very beginning, the publishing industry relied on books which could command a large market," writes John Feather in his still-relevant 1988 study A History of British Publishing. "The economics of production ... meant that it could not do otherwise." The 19th century brought mass literacy and a countrywide network of bookshops and publishers, but the business became ever more narrowly focused on producing commercial titles and selling them at a discount. "Booksellers could only afford to stock the most popular and fast-selling," writes Feather, "and had no space on the shelves for ... perhaps more worthwhile works which would sell more slowly and in smaller numbers. The bookshops ... were being squeezed out of business as a market mechanism for serious literature." By the 1890s, so many bookshops had closed and serious books were becoming so marginalised that a consensus formed that book discounting should be banned: the net book agreement was the result, and came into force on 1 January 1900.

For the next three-quarters of a century, British publishing and bookselling were diverse, slow-changing enterprises, relatively tolerant of high-minded books and "ramshackle to the cold business eye", as John Sutherland put it in a 1978 study of the book business. The arrival of state funding for libraries further softened the environment for cerebral writers. In 1965, Britons borrowed 10 books for every one they bought. "With any serious non-fiction book," says Clare Alexander, who entered publishing in 1973, "you knew you could sell 1,500 to the libraries." This enabled mainstream publishers to profitably put out books whose high-street sales were barely in the hundreds - and whose content can seem startlingly uncommercial by current standards. In 1975 Jonathan Cape published Leninism Under Lenin, a labyrinthine theoretical work by the Belgian Marxist historian Marcel Liebman. An equivalent work nowadays would be issued in Britain by a small academic press.

Yet the old British book business had its downsides. Bookshops were often dusty places, glacial in their book-ordering processes and off-putting to young or less educated customers. Even the influence of libraries, Sutherland argues, was not always benign: their preference for books that could be read in a fortnight, the standard lending time, helped keep postwar British writing terse and cramped.

But the tweediness of it all can be overstated. In 1935, in the middle of the depression, Penguin introduced the mass-market paperback to Britain, sold at first through branches of the brash American-owned chainstore Woolworth's, prefiguring today's supermarket book trade. Penguins were initially criticised as crassly commercial and middlebrow, yet soon became seen as a new, accessible form of quality publishing. In the late 1940s, the Better Books chain pioneered the idea of the bookshop as a bright and appealing space, "a social centre with a coffee bar, poetry readings and other literary events", notes Randall Stevenson in The Oxford English Literary History. Meanwhile, wider social changes, such as the growth of higher education, and technical bookselling ones - the introduction of "tele-ordering" in 1979, allowing books to be ordered in days rather than weeks or months - gradually created a bigger potential market for serious titles.

In the 1980s, that market finally materialised. Tim Waterstone was an unemployed man with six children who had already been a tea broker in India, a manager for a brewer and, most recently, the overseer of a disastrous attempt by WH Smith to set up a subsidiary in America, for which he had been fired. In 1982, he used his severance pay and money from friends and relations and the NatWest bank - the latter through the Conservative government's loan guarantee scheme for entrepreneurs - to set up a bookshop in a prosperous part of west London, which was relatively unaffected by the early 1980s recession. The rest of the Waterstone's story has long become bookselling legend: the new shop's daringly deep and heavyweight stock; its unfusty decor and helpful staff; its armchairs for browsers and friendly opening hours. For the next decade and a half, Waterstone's added branches, evangelised for "serious culture", as Waterstone characterised his books, and made literary biography and enigmatic travel writing seem viable high-street products.

New readerships appeared. "In the 90s," says Sutherland, "just before the pension penalty for early retirement came in, there was a mass retirement of teachers. Suddenly, there was a vast number of extremely competent readers who had a lot of time."

The book boom, too, was part of a broader cultural surge that produced the Independent, Channel 4 and scores of new television production companies. The free-market country being created by Margaret Thatcher, however much liberal writers might deplore its harshness, was opening up new possibilities for serious culture, while the non-market mechanisms that protected it, such as the net book agreement, remained largely in place.

During the 1990s this happy equilibrium between commerce and art in the British book business began to break down. By 1989, Waterstone's, like many new 1980s businesses, found that it had expanded too fast and borrowed too much money. Waterstone sold his bookshops to his old corporate foe, WH Smith. Gradually, over the next dozen years, the shops began to stock a narrower range of books.

To a certain extent, Waterstone's was responding to wider developments. Bestseller lists had been published in Britain since 1974, but it was only in the 1990s, with the belated installation of electronic point-of-sale technology in most bookshops, that accurate sales figures for every title became available. Meanwhile, British publishing, which had seen many of its old independent firms taken over by big corporations in the 1980s, had become much more business-oriented. By the mid-1990s, Neil Belton says, "a lot of bigger publishers were ambivalent about the net book agreement". Together with many booksellers, they thought that the freedom to discount titles would improve their profits. In 1995, the agreement in effect collapsed.

That same year, Amazon started selling books via the internet - making even the most rarefied titles universally available, at least in theory, but also offering books at deep discounts and beginning slowly to drain bookshops of their customers. By 2000, British bookselling was beginning to resemble its 19th-century self again: highly competitive, more interested in clever price promotions than clever books. That summer, Waterstone's sacked the manager of its popular Manchester branch, Robert Topping, for refusing to narrow his eclectic stock in favour of bestsellers.

Nine years on, Topping is still in bookselling. He owns and runs two shops, one in Ely in Cambridgeshire and one in Bath. If you like serious books but usually go to the chains, visiting a Topping shop is initially a shock, but then deeply reassuring. "Topping & Company Booksellers of Ely" says the archly old-fashioned sign above the door. Inside, the front of the shop is full of solid biographies, footnoted histories, books on classical music, painting and religion. There are no price promotions, no author posters, no prominently displayed celebrity titles; just plain but expensive-looking wooden bookshelves, neatly jammed with books from the floor to the ceiling and covering every wall through three storeys of small rooms. If you are looking for a John Banville novel, there are seven titles, rather than the couple you usually find in a modern bookshop. If you like the late JG Ballard, there is his genial recent autobiography but also The Atrocity Exhibition (1970). There are newspaper reviews carefully cut and mounted on a pinboard.

Topping is a vicar-ish man in cords and spectacles, but he is not some airy nostalgic. "In the age of the internet, you have to have as wide a stock as you can," he says. "I have to pay the bills myself, so I can see if it works." The computerisation of bookselling, he goes on, ought to help rather than harm serious books: "Distribution is faster, ordering is faster, so a shop can buy single copies and then restock." Is there any sort of serious book that he does think is becoming obsolete? He looks blank for a few moments. "There is this thought that the three-volume life doesn't work these days ..." He pauses again. "Does it work? I suppose not ... But if you believe enough, you can make a book sell."

His shop is busy. Topping chose its site carefully: Ely is a pretty place full of tourists and retired academics, 20 miles from the nearest chain bookshop. But he thinks location is not central to selling serious books: "My hunch is you could do this anywhere."

Belton agrees. "I don't see any evidence that readers are unwilling to grapple with serious ideas in book form, as long as the book is readable. You always hear nonsensical things: 'People aren't interested in science books any more. People aren't interested in history.' That's so wrong. There will always be new subjects, new syntheses, in every field." Peter Straus adds: "In the early 90s, people said political memoirs didn't sell, and then there was Alan Clark's diaries. Anything's possible if the book's good enough." Clare Alexander says: "I don't think the readers of serious books have disappeared. What's happened is a breakdown in delivery. From October onwards - a quarter of the year - bookshop budgets are absorbed by celebrity books."

Some aspects of the life of a serious book have probably changed for good. Anyone who has been writing them for mainstream publishers in the last decade, as I have, will have sensed the new pressures and opportunities: to get your book into the shops at the optimum time of year, to be realistic about its commercial prospects, to promote it through the ever-multiplying media. Randall Stevenson, who is the head of English literature at Edinburgh University, is an advocate of picking your way through dense postmodern texts, yet he senses a new deference in non-fiction to impatient readers. "I read popular science, and it drives me round the bend, all the attention-grabbing and cute fact boxes." The packaging and titles of serious books may also sugar their contents a little more than they used to. Colin Robinson says: "There's quite a retro quality to even the most serious books now. Novels with an old-fashioned soldier on the cover. Books called The Lost City of X."

The internet could have something to do with this. The American scientist Maryanne Wolf, in her book Proust and the Squid: The Story and Science of the Reading Brain (2007), shows that how we read, and what we are easily able and therefore willing to read, is not set, but depends on the kind of texts we are used to interpreting. "I do wonder," she writes, "whether typical young readers view the analysis of text and the search for deeper levels of meaning as more and more anachronistic because they are so accustomed to the immediacy ... of on-screen information."

This may be too pessimistic. Research into the internet's effect on reading is in its infancy. Despite decades of predictions to the contrary, the appetite for demanding non-fiction has survived the advent of newspapers, radio and television - and, in Britain, a popular culture with a particular ability to absorb talent and themes that in other countries would be channelled into grand state-of-the-nation volumes. In fact, many publishers think the noise and immediacy of the web will make slow, quiet immersion in a book seem more, not less, appealing. And books, unlike most digital media, are not directly dependent on recession-affected advertising revenues.

Other economic and social trends remain favourable: the growth of higher education; the proliferation of literary festivals; the falling costs of book production. Tellingly, more people than ever are writing books. "People are infatuated with the romance of writing," says Sutherland. "I can't tell you how many students of mine I recommend an agent to." Dying artforms tend not to attract so many new practitioners.

The crisis in serious non-fiction has probably been overdone. There is a crisis in British bookselling, thanks to the internet, the recession and the particular competitiveness of the British high street - Alexander cites the ever-increasing rents for retail premises. Some non-fiction genres, such as literary biography, are in decline, at least for now. But other serious genres, such as economics and nature writing, are on the rise. Most types of book go through these cycles of boom and bust. In unsettling times, books that try to explain the world may flourish.

In truth, it is too early to tell: serious non-fiction takes time to research and write and sell. But in the meantime, it may be a good idea for authors of such titles to be realistic about their place in the economic order. As John Feather writes in his history of British publishing, before Waterstone's, before agents and advances, before the invention of the modern book business: "The medieval author worked for himself, for God or for a patron, or indeed for all three." I'm not sure that career path would be so popular now.