According to the current Wikipedia entry, "buildering (also known as urban climbing, structuring, or stegophily) is the act of climbing on (usually) the outside of buildings and other artificial structures." Naturally, an activity of such dubious legality is carried out away from information gatherers and statisticians. Even so, a growing number of websites and youtube videos suggest an ever-growing trend.

But, it isn't a new one. I recently heard a group of urban climbers (builderers?) discussing how long they had been at the sport while watching one of their friends clambering up a drainpipe. "Since long before that James Bond film" was the general consensus, as was the fact that hanging off concrete was their "soul". I couldn't resist a smirk at their adolescent craving for authenticity; too embarrassingly reminiscent of my own absurd teenage pride in imagining myself to have championed trip-hop and baggy trousers before "it all went mainstream".

But the climbers weren't as daft as I looked. I've just read a 1930s book that not only lends credence to their claims, but also helped me understand why they might talk about their alternative interaction with urban architecture in such spiritual terms.

This slender volume is The Night Climbers of Cambridge, authored under the alluring pseudonym Whipplesnaith. First printed in 1937, it spent long years out of print, an object only of cult interest among the Cambridge climbing fraternity. On its 70th anniversary, however, it was reprinted by the admirable Oleandar Press and has since sold more than 4,500 copies – not bad for a book costing £17, which the major book chains have (foolishly) refused to stock, and which seems to have been written for and about a bunch of posh students with a reckless disregard for their own safety.

But the reason this book has captured the imagination becomes apparent as soon as you read the back cover:

"As you pass round each pillar, the whole of your body except your hands and feet are over black emptiness. Your feet are on slabs of stone sloping downwards and outwards at an angle of about thirty-five degrees to the horizontal, your fingers and elbows making the most of a friction-hold against a vertical pillar, and the ground is precisely one hundred feet directly below you.

"If you slip, you will still have three seconds to live."

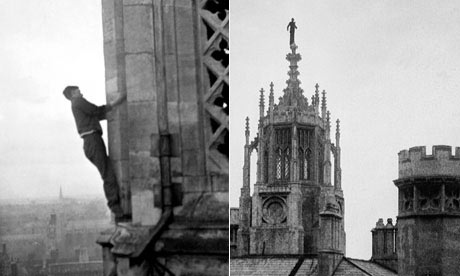

Inside, it's even better. The new edition contains some fine photographs of 1930s students (some in blazer and ties) at quite astonishing angles on famous Cambridge landmarks, beautifully illumined by the moon and camera flashes. These alone would be enough to sell the book, but they pale into insignificance against the delightful musings of Whipplesnaith (in reality, Noel Symington).

First and foremost, these notes provide a practical guide to getting up the outside of Cambridge landmarks; interesting in and of itself and, apparently, still useful. Who wouldn't be intrigued by the alternative view it provides of so many world heritage landmarks? Who knew, for instance, that the massive stone domes on top of the Fitzwilliam Museum are actually fakes made of metal? Who knew the best way to traverse the outside of the Bridge Of Sighs?

But such superficial pleasures aren't the half of it. This book is also a wonderful evocation of a lost generation. In some ways, the Night Climbers were the beneficiaries of obscene privilege; young men whom far older policemen (or "Roberts") still referred to as "sir", and for whom the idea of a student loan would seem like a joke. But they still had their share of travails.

Just as it's possible to suggest that those currently seeking highs on city rooftops are reacting against their cotton-wool upbringings, so Whipplesnaith's stories of death-defying derring-do in Cambridge say a lot about those whose parents had lost so much in the first world war but who themselves were (for now) bereft of action and significance. It's another side of Brideshead Revisited: a Cambridge not, as Whipplesnaith has it, of "morning coffee in the cafés, beer drinking, hilarious twenty-first birthday parties" but of "a jumble of pipes and chimneys and pinnacles, leading up from security to adventure".

Certainly, you can recognise a character type in the men who struggled to the top of John's Chapel and then refused to say anything about it: "Lest others should attempt the ascent of this terrible climb and perish, they swore themselves to secrecy (telling only enough people to ensure perpetuation of their epic) and went off to try Everest instead."

Finally, as all the above quotes amply demonstrate, the book is also worth reading simply because of the excellence of its prose. It enables even those who – like me – prefer to use the stairs to get to the top of buildings to experience some of the vertiginous pleasure of night climbing; the serene beauty of a moonlit ascent of Kings College chapel, the joy of mastering a well-secured drainpipe, and the wonder of watching the dawn rise over the roofs of Cambridge.

It is, in short, a book as wonderful as it is weird – and the new generation of urban climbers should be thanked for making it popular once more.