The TV chefs of the 70s and early 80s were, on the whole, a pretty uninspiring bunch. There was Fanny Cradock and her ridiculous monocled husband, Major Johnnie. There was the wokwielding Ken Hom and the pompous, patrician Derek Cooper. Madhur Jaffrey introduced the curry powder-reliant Brits to fresh coriander and fenugreek, while Marguerite Patten was occasionally wheeled on to bang on about rationing. And then there was Delia, presiding in her matronly fashion over this motley crew, dispensing reassuring advice about Victoria sponges and gravy.

Who provides the link between these relics from TV's past and Gordon, Jamie and the other expletive-spouting celebrity chefs of today? According to David Pritchard, author of Shooting the Cook, it is Keith Floyd, the bibulous, bow tiewearing restaurateur from Bristol who made it big in the 80s with his run of shows featuring every possible variety of on-the-hoof cookery. Before Floyd came along, food programmes were safe, predictable and dull; their target market was mainly housewives.

Floyd introduced an element of chaos, even danger, to proceedings, something which, Pritchard suggests, broadened the appeal of cooking shows, making them appeal for the fi rst time to men. "When Floyd came on to our screens," he writes, "he gave men a clear and open invitation to get into the kitchen and have a go for themselves. Forget about exact ingredients, pour yourself a glass of wine and relax."

Pritchard is well-placed to understand Floyd's appeal, because he played a large part in creating it. A long-serving BBC producer based in Bristol and later Plymouth , Pritchard first encountered Floyd at his restaurant, Floyd's Bistro, in the early 80s. Although their first meeting wasn't propitious – Pritchard was told to "bugger off" when he revealed that he worked in television – he soon talked Floyd into making a series about fish.

Regional TV in those days was a pretty ramshackle operation; Pritchard

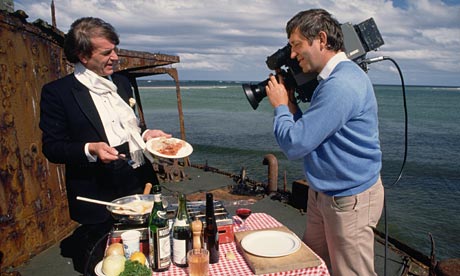

had to work with a tiny budget and only one camera. The programmes, as a consequence, had a makeshift feel. With minimal planning or preparation, Floyd and Pritchard would simply turn up somewhere – a trawler boat, a country hotel – and film Floyd cooking, unscripted and with a glass of red wine at the ready, using whatever facilities were available. Although Pritchard's bosses doubted the formula could work, Floyd on Fish proved an instant success and the pair went on to film another seven series.

In Shooting the Cook, Pritchard tells the story of his years working with Floyd, as well as with his other big discovery, Rick Stein. As you'd expect, the book is packed with tales of larger-than-life antics and wacky experiences: the time, at a fish market in Newlyn, the stallholders stuck a label to the back of Floyd's Burberry trenchcoat saying "Fresh Prick"; the time Pritchard witnessed a 2,000-serving paella being cooked, aided by cranes, in Benidorm. On the whole, though, it's a rather sombre tale. What quickly becomes clear is that Pritchard and Floyd's relationship was always troubled, marked by envy and rancour on either side, as well as affection. Floyd, not surprisingly, had a colossal ego and resented being bossed about by Pritchard, whom he regarded as an ignoramus. Before moving to Bristol, Floyd had run a successful restaurant in France and he constantly reminded Pritchard just what a provincial upstart he was, with his liking for roast beef and bitter over cassoulet and Bordeaux. The pair's disagreements eventually caused them to fall out and they didn't see each other for 16 years. In the book's final chapter, there's a sad account of a recent reconciliation in Phuket, where Pritchard encounters Floyd, drunken and jobless, still harping on about how Pritchard and others like him got him into "this fucking mess".

The irony is that Pritchard, though a late starter in gastronomic terms, and defi antly patriotic in his tastes, actually has a genuine love for food and the best passages in Shooting the Cook are when he communicates this. There are brilliant descriptions of coming of age in the 60s and 70s, subsisting on things like tripe and onions and tinned pilchard salad and encountering such exotic fare as Lurpak butter and spaghetti bolognese for the first time.

In fact, if the book has a problem, it is that it contains too much about Floyd and Stein and not enough about Pritchard. All the telly stuff comes across as a bit of a distraction from what Pritchard really wants to talk about, which is his own passion for food. In this sense, I suppose, Pritchard has remained true to his role as producer, deploying his talents behind the scenes while his "stars" take centre stage. A good and interesting book might have been an even better one had he allowed himself to hog the limelight a little more.