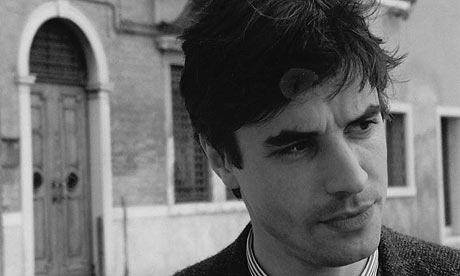

Mick Imlah, who has died at the age of 52, was one of those rare figures in British poetry: a truly literary protagonist. Part of a generation for whom it became fashionable to disavow literary seriousness – in CVs which instead drew attention to any other feature of the poet's life – Imlah, while popular and gregarious, committed his working life to very best practice. With his death we've lost not only a major poet but a major editor, too.

Before last year's publication of The Lost Leader, Imlah's only collection – with which he sprang to prominence as part of the New Generation Poets promotion – had been 1988's sparky, witty Birthmark. As always, when a poet of Imlah's seriousness emerges, this, his full-length debut, demonstrated accomplishment as much as promise. There followed 20 years in which a next collection was rumoured, but not released by its perfectionist author. As in the best stories, this wait was absolutely to pay off.

The Lost Leader, which won this year's Forward Prize and was shortlisted for the TS Eliot, is a profound, and profoundly-anchored, take on history and identity. Its exploration of Scottishness and belonging leads steadily – and compendiously – to a study of what it is to be human within that experience. It's also a volume conspicuous for unassailable technical excellence. Through its rich formal poetics, in particular, Imlah's poetry anchors itself to the 19th-century tradition of public, political poetry: a tradition after Wordsworth and Tennyson, in which the wider canvas provides the opportunity to clarify, but never to simplify, those tensions between the personal and the political.

This, however, is not the best of stories. Imlah's last book was published only after he was diagnosed with the motor neurone disease that has claimed his life. The Lost Leader reads something like a selected poems, not only because of its unusual length (128pp) but because it does in fact collect the poems of its author's maturity.

Also published in 2008 was Imlah's selection from the poems of Edwin Muir (he produced a selected Tennyson, prepared like the Muir for Faber, in 2004). This burst of publishing activity was of course no growth spurt: that had already been happening during Imlah's 16 years as poetry editor of the Times Literary Supplement, a post in which he shaped the taste of a critical generation. If the TLS allowed him to extend his critical practice beyond the range of personal activity – and to inform the contemporary academic canon – his earlier work, as poetry editor at Chatto and as the editor of Poetry Review, showed Imlah to be an iconoclastic and supremely intelligent reader of poets both known and unknown. Much that is healthy in British poetry today remains a legacy of that work.

Imlah was part of the tradition of great British poet-editors, from Eliot to Hamilton and on to Paterson and Robertson, who demonstrate that there might be more to a life in poetry than narrow narcissism. Lost Leader indeed: his death feels like the end of an era.