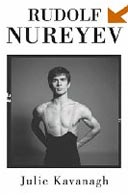

Rudolf Nureyev: The Life

by Julie Kavanagh

Penguin £9.99, pp787

Rudolf Nureyev changed the face not only of ballet, but of ballet celebrity. His defection from the USSR in 1961 saw his image blazed worldwide, and his passionate onstage partnership with the much older Margot Fonteyn held the world agog. He became one of the most closely scrutinised men of his generation. Hours of performance film survive, and there have been at least a score of biographies. But Nureyev was a private and often lonely figure. He parcelled out slivers of intimacy to his dancer colleagues, the society hostesses who wined, dined and indulged him, and an endless succession of male lovers, but none of them was trusted with the whole story.

Julie Kavanagh didn't know Nureyev, but she is advantageously positioned in the ballet world, and her biography - the best part of a decade in the writing - comes closer to telling this story than any other account. Her researches in Russia have uncovered revealing details of Nureyev's early career at the Kirov Ballet in Leningrad, including the story of his first male lover, an East German ballet student who encouraged him to defect. In the West, Kavanagh's scrupulous interviewing of the dancer's high- and low-life acquaintances, many of whom have previously remained silent, gives her account unprecedented authority.

But Kavanagh is more than just an assiduous sleuth. As her 1996 biography of Frederick Ashton, Secret Muses, proved, she is an accomplished prose stylist with a gift for bringing dance alive. She succeeds, where others have failed, in summoning up Nureyev's 'feral power' and 'savage intensity' in performance. She shows how, through a complex interweaving of personal insecurity and artistic self-belief, he created the Nureyev myth: the idea of himself as a super-being to whom society's rules simply didn't apply. 'When you see me dance, you see a part of God,' he once said.

Balancing sympathy with a forensic eye, Kavanagh deconstructs the myth and reconciles her subject's apparently warring aspects: the quasi-religious work ethic and the sluttish promiscuity, the generosity and the selfishness, the devouring intellectual curiosity and the infantile tantrums. The result is the definitive portrait.