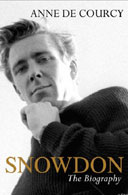

Snowdon: The Biography

by Anne De Courcy

456pp, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, £20

What has worked for Lord Snowdon all his life almost works in this hagiography. In a little world populated by England's most ghastly and dim, he again appears to enormous advantage; abrim with style (of a sort), charm (if you like that kind of thing) and energy (mainly for sex). It is worth remembering, of course, that in this context, the same would apply to the average tomcat.

When, to his enormous satisfaction, the priapic photographer (then called Antony Armstrong-Jones) made it into the royal family, it was easy for this spoiled little pixie, with his extra-tight drainpipes and mesmerising bouffant, to be mistaken for a much-needed corrective to the snobbery, stupidity, and stolid sybaritism of the nation's top inbreds. Simply by being a society photographer, as opposed to a titled nothing, Snowdon was able to portray himself as an arty free spirit, almost an intellectual, under whose tonic tutelage, it was imagined, the Windsor troupe might evolve into a more acceptable, near-human subspecies. The success of this experiment can be quickly judged simply by looking at recent pictures of Prince Harry and his girlfriend, Chelsy Davy.

One of the most interesting facts in Anne De Courcy's book is that Snowdon never reads. Another is that the most iconoclastic thing he ever did, as a royal, was to wear polo necks instead of ties; a level of democratic endeavour that proved eminently acceptable to his in-laws, who soon discovered that they preferred the dashing, yet reliably subservient, Tony to foul-tempered Princess Margaret. It helped that in all the key matters relating to status, the exploitation of servants, and unembarrassed grovelling, arty Armstrong-Jones was everything they might have hoped from the son of Lady Anne Rosse, or "Tugboat Annie" - so called "because she goes from peer to peer". Tugboat Jr quite eclipsed her, as he pranced between Queen and Queen Mother, enchanting both ladies to the point that, even after the divorce from Margaret, whom he treated abominably, they pined for his company at Balmoral.

But, as De Courcy stresses, the decades of marital feuding and hate notes ("you look like a Jewish manicurist") had started as a genuine romance. Meaning that Snowdon, who liked to keep several women on the go, may have confined himself to no more than one simultaneous affair, or at most, two, while he was courting the unsuspecting Margaret. Let us hope this provides some consolation to the British servicemen whose pay was docked by sixpence apiece in 1960 in order to provide the pair with a wedding present: "a small marble-topped commode", De Courcy reports.

The exact nature of the qualities that captivated Princess Margaret, her family, Snowdon's legions of ill-treated lovers and, most recently, the author of this dazzled tribute, remains, even after 400 pages, obscure. Loyal De Courcy passes on reports of an extremely large penis, but that can hardly account for Snowdon's effect on Prince Philip. Or, later, on Christopher Frayling, rector of the Royal College of Art, who said Snowdon was "the best provost we ever had".

Was it wit? None is recorded here. Young Snowdon's speciality was nasty practical jokes, such as putting dead fish in girls' beds. It was the grown-up Snowdon's, too: "they would sortie out to the houses of neighbours they knew to be out or away", De Courcy hilariously reports, of the earl and his chums, "and rearrange all the furniture".

Looks, then? As irresistible as Snowdon may have been in the 50s and 60s, and even the 70s and 80s, it hardly accounts for the posh old shagger's continuing appeal, not only to the author of this homage, but, incredibly, to an attractive young journalist, Melanie Cable-Alexander (by whom he fathered a child), and, more recently, to Marjorie Wallace, the mental health campaigner who may now be remembered, above all, for her ungovernable passion for a past-it prankster. What do they talk about, over lunch at the Caprice? Much as one would like to imagine the lovebirds exchanging insights on photography, ornithological matters or disabled access, there is little evidence, from the taped conversations that became this book, that the activities which have given substance to his reputation actually interest the earl anything like as much as gossip, sexual intercourse and money. Even quite small amounts of money. There is mention, at one point, of "postage". A section about Snowdon's child by Cable-Alexander (one of two children whose paternity he at first questioned) specifies the fearful sums demanded by the little chap's prep school, "from £2,375 a term". And that comes on top, Snowdon emphasises, presumably in a bid for sympathy, of "gas, electricity and telephone services, bills from Berry Bros, council tax of £1,377 ... "

Although De Courcy tries valiantly to generate admiration for various artistic and charitable triumphs, for Snowdon's photographs of "slum children", and his campaigns on behalf of disabled people, her efforts are continually nullified; not by her obvious partiality, but by yet more evidence of Snowdon's awfulness, as volunteered to her, exclusively, by himself. There are reasons, De Courcy shows, why Snowdon should have emerged so deceitful, manipulative and cruel; so mean, boastful and silly. His father sounds silly too. His mother, Tugboat, once she'd divorced and remarried, more or less ignored him until he bagged Margaret. He had polio as a child, leaving him with a dodgy leg. Then again, you'd think that half a century of adulation, plus a family, experience and a bit of maturity would eventually even things out. On the contrary. It is only, one suspects, because he is using a wheelchair that Snowdon does not, even now, creep out of a night to plant dead fish or rearrange people's furniture.