Lindsay Nicholson made the saddest remark I've ever heard from an author - 'I always wanted to write a book,' she told me. 'I just didn't want it to be this one.' This one is Living on the Seabed: A Memoir of Love, Life and Survival (Vermilion, £9.99) and it tells the harrowing story of how she lost first her husband, then her daughter to leukaemia.

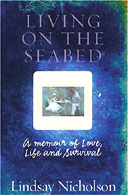

I must say the title and the cover look as though they are destined for those dim shelves marked 'Spiritual' in the bookshops, but, actually, the narrative rattles along as briskly as any thriller. And, after so much heartbreak, Nicholson's story has a happy ending. Two years ago, at the age of 46, she married again.

She is the editor-in-chief of Good Housekeeping, so I expected her home to be some sort of domestic-goddess vision of swags and flounces but actually it's quite bare. She, too, is not what I expected - briskly spoken, direct and with a surprisingly dirty cackle of a laugh. But, just occasionally, her eyes brim with tears. 'If you'd come here three years ago,' she tells me, 'the room would have been six feet shorter, it was so full of Ellie's things. Her books, her clothes, her toys, all her birthday cards. It wasn't a home, it was a mausoleum. And poor Hope would be told not to put her things there because that's where Ellie's things were. Terrible!'

Ellie is the daughter who died; Hope, now 12, is the younger daughter, born after her husband's death. She met her husband, John Merritt, when they were both doing the Mirror Group training scheme in Plymouth, and married in 198l. Alastair Campbell and his girlfriend, Fiona Millar, were fellow trainees and became their best friends.

After training, they moved to London, where Lindsay worked in women's magazines while Merritt forged a distinguished career as an investigative journalist - John Pilger called him the finest journalist of his generation - first on the Mirror and then on The Observer. Their first child, Ellie, was born in 1988.

But then, in 1990, John complained of tiredness and an unstoppable nosebleed and was diagnosed with leukaemia. His mother had died of the disease when he was a schoolboy, but, amazingly, Lindsay says she never thought about him dying: 'I was 32 with a new baby and you don't think about death. Basically, we just chose to ignore it a lot of the time. Our attitude was: this leukaemia thing, we're having none of it, we're going to pretend life is normal. I suppose it does make us sound really dim, but I think you do go into this sort of coping mode.'

John coped by working; he only took four weeks off in the whole two years he was sick. He read Primo Levi and books about the Holocaust: 'He was very concerned with terrible things that happened that needn't have happened, rather than what was happening to him which couldn't be stopped.'

She coped by keeping the house spotlessly clean to prevent opportunistic infections; once, she plunged her hands into neat bleach to make sure they were germ-free. 'I scrubbed and scrubbed and scrubbed this house; I wore things away with scrubbing them. And it was not uncommon for me to make a complete meal, throw it away, disinfect the entire kitchen and start again. And then sometimes throw that away, too. Quite obsessive behaviour, really. But a lot of the time he had no immunity.'

Throughout it, they enjoyed a good sex life. In her book, she says: 'I'm sure some people think that if you are terminally ill, sex is the last thing on your mind. In fact, I would say, the reverse is true - it can become a celebration of life.' She was overjoyed when, almost two years after John's diagnosis, she found herself pregnant. 'I always wanted another child and I didn't see why, just because John was ill, I should not have one. I didn't think it was very likely to happen. But all the way through, I adopted a rather bloody-minded, pig-headed attitude to things - thank God! Because at least I've got Hope.'

Anyway, she never believed John was dying. She was shocked to the core when one morning he said casually: 'I don't think I'll live to see this baby', before asking her if she wanted a lift to work. He died a few weeks later, in August 1992. She was left a four-months pregnant widow with a three-year-old daughter and poleaxed by grief.

She was sure her baby would be born dead. In fact, Hope - she and John had chosen the name together - was fine, but Lindsay continued to feel hopeless. She only began to recover when she returned to work four months later. She found a sort of clarity in work that she didn't find at home. 'You just do it and, if you do it badly, you think, well it's not as bad as your husband dying, whereas before I faffed and fretted without ever achieving so much.'

In fact, her career took off like a rocket after John's death - she was appointed launch editor of Prima, and was made editor of the year.

She continued to mourn John, but four years after his death, she says her life was 'really rather enviable'. She had a job she loved, the girls were happy and thriving at school, they could afford glamorous holidays and she even bought herself a Porsche. But then, in November 1997, Ellie caught a cold she didn't seem able to shake off. The GP sent her to the hospital for blood tests and the diagnosis came back the same day - leukaemia.

Ellie was transferred to Great Ormond Street hospital where Lindsay stayed with her for the next eight months while she was undergoing chemotherapy. Incredibly, she not only held down her job at Prima but also launched two new magazines while she was living in Ellie's tiny hospital room. Ellie appeared to be doing well at first, but it seemed to take her longer each time to recover from chemo and in June 1998 she died.

After Ellie's death, Lindsay went into years of what she calls 'living on the seabed' - functioning, just, but in permanent darkness. She believes she was literally 'mad with grief'. She put on weight, ballooning from a size 12 to a size l6; she drank too much and threw up at parties. Her palms had scars she calls her 'stigmata' from where she dug her nails in during her sleep.

She would go to social events and see everyone chatting and laughing and want to cry out: 'Don't you realise everyone is dying!' Friends, she says, 'melted away like snow'. Some never contacted her again and avoided her if they saw her; even the ones who stayed loyal found her difficult to be around.

One of the friends who didn't melt away but stayed solid as a rock was Alastair Campbell. He visited Ellie all the time she was in hospital, was a pallbearer at her funeral (and at John's) and later ran marathons and triathlons and raised more £600,000 for leukaemia research. He and Fiona Millar took Lindsay on holiday with them, where Peter Mandelson served as childminder and nappy-bag carrier.

She has learned a great deal about herself through writing this book: 'I suppose what came through is this juxtaposition between the kind of person that I am that made it easier for me to cope but harder for me to accept death. I am very determined, very energetic and very driven, so that being pregnant, bereaved, having a three-year-old child and a full-time job, I just did it.

'The house was spotlessly clean, we never ran out of milk. Those things, which made me cope very well on a practical level and made me advance in my career were also stopping me from accepting death. So it was this kind of push-pull aspect of my nature and it was only when I gave up fighting, when I couldn't fight any longer ... only then did I start internally to process what had happened, which led, eventually, to being able to forge a relationship.'

She went through years of psychotherapy, hating it at first but eventually acknowledging its usefulness. What also helped, she believes, was buying a little house in Essex that needed massive work, so she would escape there with Hope at weekends. And then, at Christmas 2002, she started thinking about selling her house in London and saw that it was a mausoleum. She packed up all Ellie's things and put them in storage. Then she asked an estate agent to value the house.

In the end, she decided not to sell the house, but she fell in love with the estate agent and married him last summer. Nowadays, if someone asks if she has children, she says: 'Yes, my daughter is 12.' But, she adds firmly: 'What I would never say is I only have one child. I will always have two children.'