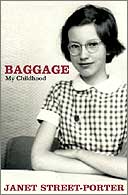

Baggage: My Childhood

by Janet Street-Porter

Headline £16.99, pp276

I have a confession. I may be the only journalist in London that Janet Street-Porter hasn't reduced to tears (which says more about my slow-burn career than about her). I've never worked with - or for - her, so technically I'm a blank slate. OK, we all know the famous stories of tantrums and tiaras, the screaming matches with Kelvin MacKenzie when she joined L!ve TV, the near-revolt by staff when she became editor of the Independent on Sunday, but I've always felt a degree of amusement (affection even) at watching her antics from the sidelines. No one likes a bully. But mouthy, pugnacious, elitist ... she is good copy.

Of course Janet is her own finest creation. Especially when you think how little she started out with. First there was the unhelpful genetic lottery - lank hair, skinny physique, frilly teeth. She was bookish and clever and insolent, which went down badly in working-class Fulham in the Fifties.

She compensated by refusing to believe her parents really were hers, and tried to 'eliminate' her sister by pushing her downstairs.

She knew she had to get out of this emotionally-repressed household. With a title like Baggage, it's clear where the book is heading. Yet it is surprising. True the vitriol flows towards the end, as the young Janet despairs of ever fleeing suburbia for groovy London. But the first half is devoted to trying to work out why her parents ended up the way they did.

In fact Cherrie, her mother, emerges as a larkish, flirtatious young woman eventually worn down by a controlling husband. You sense Street-Porter's frustration that she never got to see this side of her.

The restraint in the early pages is impressive when she had to put up with slaps, rebukes, rejections, a belt behind the door.

Her family emerges as weird. Terrified that the neighbours would gossip when Janet caught dysentery, they bundled her over the back wall into a waiting ambulance. And their own sexual incontinence (both were married to others when they met) didn't stop them being harsh moralists. And they were thoughtless. A move to suburbia gave their daughter hours of daily commuting to school.

Not that Street-Porter emerges well. A series of mentors and lovers are cultivated, then cast brutally cast aside. 'My attitude to sex was totally childish.' She knows she is clever but lacks focus. One college tutor says: 'She could make astonishing progress with brilliant results or deteriorate to the point of disillusion.'

But what is overwhelming is her seething, irrepressible hunger for life. J S-P is self-made: 'I knew I was starting on a long journey alone.' For cultural historians, Baggage offers a fascinating snapshot of Sixties London - nightclubs, modish Italian films (J S-P and her set were extras in Blow-Up) and barmy, extravagant clothes. 'I cut an outlandish figure - think of a Dalek played by a string bean and you've got the look.'

There's something faintly outrageous about an autobiography which ends at 20 when J S-P finally flounces out of the family home, telling her mother: 'I can't stand being with you one fucking minute longer, you miserable old cow.'

Style isn't Street-Porter's strong point. She relies on a gripping narrative, concisely told. One senses not a huge amount of time went into the writing. It's lazy, partisan, audacious - not unlike the writer herself. But a whole lifetime went into the material. And that in itself makes it remarkable.